Jun 6, 2015

Antibodies Part 1: CRISPR

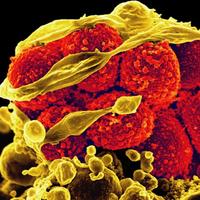

Hidden inside some of the world’s smallest organisms is one of the most powerful tools scientists have ever stumbled across. It's a defense system that has existed in bacteria for millions of years and it may some day let us change the course of human evolution.

Out drinking with a few biologists, Jad finds out about something called CRISPR. No, it’s not a robot or the latest dating app, it’s a method for genetic manipulation that is rewriting the way we change DNA. Scientists say they’ll someday be able to use CRISPR to fight cancer and maybe even bring animals back from the dead. Or, pretty much do whatever you want. Jad and Robert delve into how CRISPR does what it does, and consider whether we should be worried about a future full of flying pigs, or the simple fact that scientists have now used CRISPR to tweak the genes of human embryos.